Geographical descriptions and maps of Imperial Russia

Geographical descriptions and maps of Imperial Russia

[FY 2001 Special Collection]

[FY 2001 Special Collection]

This is a collection of rare books about and atlases of Imperial Russia and its capital, St. Petersburg, written in English, German and French. They were produced/published from the mid-16th to the early 19th centuries, and are extremely rare materials covering general geography, geographical descriptions, society, culture and customs in various regions of Russia in those days.

| Form | Original |

|---|---|

| Volume | 15 items |

| Language | Several |

| Year of purchase | 2001 |

| Borrowing | No |

| Photocopying | OK (with some exceptions) |

* Introduction to Materials (Yuin Hokkaido University Library Bulletin Vol. 113, p. 13 – 15)

About the collection of geographical descriptions and maps of Imperial Russia

Yuzuru Tonai, Lecturer at the Slavic Research Center

The collection of geographical descriptions and maps of Imperial Russia consists of 15 items, including maps of major cities and various regions of the country produced in the latter half of the 18th century, Commentaries on Muscovite Affairs by Sigismund von Herberstein (1486 – 1566), who visited Russia as an envoy of the Holy Roman Emperor at the beginning of the 16th century, and books about customs and the state of affairs in Russia that were published primarily in the West from the latter half of the 18th century to the early 19th century. Although all these items fit onto only two shelves of a bookcase, they are very rare and valuable materials. In this sense, they are a worthy addition to Hokkaido University Library’s collections and are expected to benefit studies on Russia in the future. Here, I would like to briefly introduce several items in the collection.

One atlas covering various regions of Russia was mainly produced from the 1770s to the 1780s. Rather than originally being published as an atlas, it was bound together by a collector and contains 49 maps in total. Although the map producers and sizes are not uniform, in most cases, each province (Guberniya) is depicted in two facing pages measuring 50 cm from top to bottom and 70 cm from side to side. Many of the maps were produced by Jakob Friedrich Schmidt (? – 1786), a member of the Russian Academy of Sciences, and Ivan Truscott (1721 – 1786), and cover a wide variety of areas including Eastern Siberia, Russian America, Central Asia, Caucasia, the Gulf of Finland, the Baltic states, Crimea, Moldavia and Wallachia. There are also maps of cities such as St. Petersburg, Moscow and Astrakhan, as well as a drawing of fireworks launched to celebrate the coronation of Anna Ivanovna (who reigned from 1730 to 1740).

Hokkaido University Library already has a number of atlases, including one published in 1745 by the Russian Academy of Sciences, a map of western part of Russia drawn up by the Russian military’s map division in the early 19th century and a Chinese atlas published in 1737 by d’Anville. Comparing these materials with the newly obtained atlas has provided further insight into the development of Russian cartography in the 18th century.

Next, I would like to introduce Commentaries on Muscovite Affairs by Sigismund von Herberstein. He was dispatched to Moscow twice in 1517 and 1526 on diplomatic missions for the Holy Roman Emperor, and engaged in negotiations with Moscow’s Prince Vasily III (who reigned from 1505 to 1533). After returning home, he published a Latin edition of Commentaries on Muscovite Affairs (Rerum Moscoviticarum Commentarii) in Vienna in 1549, creating a sensation. It was repeatedly reprinted in Latin and German in various parts of the world, and has become a standard resource in studies of 16th-century Russian history. Although there are translations in both English and Russian, unfortunately there is no Japanese version yet.

The acquired collection contains the second edition in Latin (Basel, 1551) and the fourth edition in German (Frankfurt, 1576); both books are in good condition.

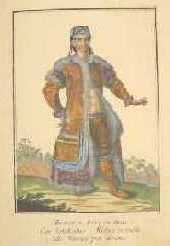

Next, I would like to highlight two collections of drawings of ethnic groups in Russia. The originals are illustrations published in 12 separate volumes from 1774 to 1776 under the title of “Russia opend, or a Collection of Clothing of All Peoples in the Russian Empire” based on the results of expeditions by the Russian Academy of Sciences. The illustrations are beautiful, made from hand-tinted copperplates, and their exotic appeal seems to have been popular with European readers. They were used in a book authored by expedition member Johann Gottlieb Georgi (1729 – 1802), entitled “A Description of All the Peoples inhabiting the Russian State, as Well as Their Daily Rituals, Beliefs, Customs, Clothing, Dwellings and Other Characteristics,” and proliferated widely as a result.

The acquired materials here are original pictures bound together into a book, and another version published in London in 1803 with English and French explanations. The latter was published as a new edition by a British painter with a design similar to that of the original, but comparison shows background omissions and emphasized beauty and congeniality to suit Western tastes.

Left: Unmarried Yakut girl (Russian edition of a Collection of Clothing of Russian Peoples); right: the British edition

While checking the newly acquired collection, I noticed that the design of this group of drawings was quoted in the supplement (collection of drawings) to Le Clerc’s Histoire physique, morale, civile et politique de la Russie moderne (History of Russia), published between 1783 and 1794, Paris), and such quotations were found for more than 30 illustrations among a total of 95. This indicates how influential the collection of drawings was.

According to Yukio Iwata, in Japan, Bunka Women’s University Library holds the French edition of Georgi’s ethnography and a rebound volume of illustrations collected from its German edition. In addition, Meiji University Library has a revised second edition in Russian. And we can add that the Slavic Research Center Library has microfilms of two Russian editions.

Lastly, I would like to draw attention to Reise in den Kaukasus und nach Georgien (Journey to Caucasia) by Julius Heinrich Klaproth (1783 – 1835). Born in Berlin as the son of a renowned chemist, he devoted his energies to the study of Chinese from his boyhood years. In 1805, he went to Kyakhta as a member of a delegation to China, picking up a good command of the Mongolian and Manchu languages and collecting a variety of materials. Immediately after returning home, he went to Caucasia and stayed there from 1807 to 1809. The newly acquired materials include a report on his stay there, published in German between 1812 and 1814, and a supplementary volume entitled “Kaukasische Sprachen.”

Subsequently, Klaproth left Russia and lived in Paris from 1815, where he made remarkable achievements in areas ranging from studies into Siberia and China to Egyptology using his impressive linguistic abilities. These included a French translation of Shihei Hayashi’s geographical work Sankoku Tsuran Zusetsu (An Illustrated Description of Three Countries, published in 1786).

Hokkaido University Library already has five of his works, but the addition of Reise in den Kaukasus und nach Georgien (Journey to Caucasia) has brought his achievements in the early days of Oriental studies in Europe all the more closer to us.

Here I have briefly introduced some of the major components of the collection. The addition of these hard-to-find items to the Russian and northern materials at Hokkaido University Library – one of the country’s finest collections of its kind – is significant, and I hope that the collection will prove useful for both research and educational purposes.