W. S. Clark and the Sapporo Agricultural College Library

W. S. Clark and the Sapporo Agricultural College Library

Eiichi Sugawara

(Hokkaido University Library)

[1]

There is currently a welfare facility called the Clark Memorial Student Center on the far south side of the Hokkaido University campus. On the north side of the building is the Central Lawn, which is surrounded by buildings and structures including Furukawa Hall, the University Library, Centennial Hall and the famous bust of Dr. William S. Clark. The University Library at this end of the southern area of Hokkaido University’s Sapporo Campus has stood there for more than a hundred years, and forms the origin of the words discussed here.

W. S. Clark spent only about eight months as the first Vice-President of Sapporo Agricultural College during the period from July 1876 to April 1877. In this short time, he performed a range of tasks, and also left his thoughts on the Sapporo Agricultural College Library in a letter he wrote at the end of his stay in Sapporo. ( Clark’s handwritten letter (page 1) Clark’s handwritten letter (page 2))

Toshiyuki Akizuki wrote:

“In December 1876, four months after the opening of the college, a two-story wooden book storehouse with Japanese spindle roofing was built over a 99-m2 area between the North Hall and the dormitory. This was the original library building – an independent facility – but Vice-President Clark seemed somewhat unsatisfied with the storehouse, which was based on a design drawn up the previous year, and he asked President Zusho for improvements in moisture prevention, daylight and the arrangement of the bookshelves. Compared with the school building, which was a sophisticated western structure, the book storehouse looks quite humble even in pictures. Furthermore, the facility did not have a reading room. A reading room (dokushobo), where magazines and newspapers were kept, was separately prepared in the North Hall. (Akizuki et al., 1980)

The letter, in which Clark requested “a range of improvements,” was dated March 17, 1877. He detailed the location of the library on campus, humidity prevention measures inside the building, daylight issues, the modification of windows and stairs and his views on books among quite a wide range of problems. He probably wrote the letter to promote a minimum number of modifications to the library before returning home in April.

Clark visited a number of facilities in Tokyo before arriving at Sapporo Agricultural College. One of these was the Library of Tokyo, which he visited on July 10, 1876. It is uncertain whether he recalled the library that he had observed more than six months earlier when he was writing the letter, and he might have been thinking of the libraries at Amherst College or Massachusetts Agricultural College as comparisons. Now, let us take a point-by-point look at the contents of the letter.

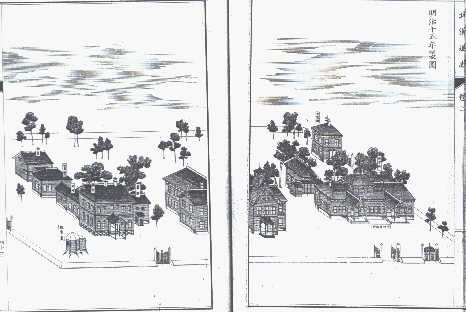

Sapporo Agricultural College Library in around 1903

[2]

Clark started with the location of the library, saying, “I have this day examined the building, and beg to make the following suggestions in regard to it.” He continued:

“In regard to the location, it seems to me altogether unsuitable and dangerous. It is therefore highly desirable that it be moved directly south one hundred feet. If this is not done, then the privy must be removed for decency’s sake.”

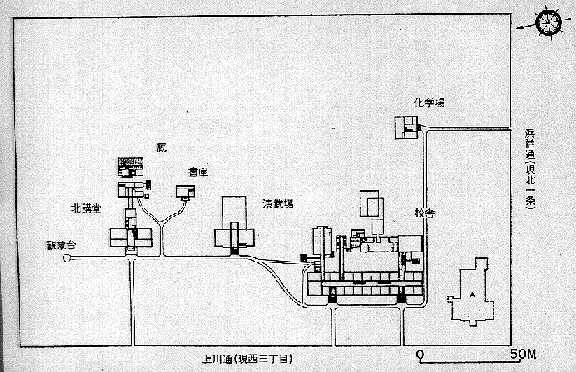

Did he really see the location as being problematic for decency’s sake in a literal sense? A look at the building allocation on the campus at that time shows that there were not as many faculties and research institutes as there are now, so it is difficult to imagine that he requested the relocation to secure more favorable access from an educational and research standpoint based on the layout of the buildings on campus. However, moving the library 100 feet (approx. 30 m) directly south would have put it in the vicinity of Drill House (constructed in 1878), bringing it halfway between the North Hall and the school building (dormitory). Whether users regard this location as the most accessible or not depends on the requirements of the time. (The buildings present on campus when the book storehouse was built were the North Hall, the school building and the lavatory on the map below.)

Map of the early Sapporo Agricultural College campus

Source: The Architecture of Sapporo Agricultural College by Takeshi Koshino

Here, we allow ourselves to recall a classical question of library science: Where should a library be located? We certainly know the stereotypical model answer that it should be in the most accessible location. The question, however, may be in the process of becoming outdated in today’s world of advanced computer and communication technologies. In other words, we now live in a time where text and information come and go beyond spatial boundaries, regardless of the locations of libraries and written materials.

[3]

Clark continues:

“The interior of the building is very badly arranged, and at present is totally unfit for books, as they would be spoiled by dampness. The upper story should be plastered overhead to exclude moisture from the roof, and there should be a ventilator.”

It can be easily imagined from this description that the inside of the building was poorly ventilated, humid and badly organized. Unlike today, acidic paper would not have been a problem, and it goes without saying that people did not have to consider the deterioration of books by copying. However, the Sapporo Agricultural College Library of the time was more like a warehouse than a library; for such a building, keeping books in good condition must have been an issue of great interest. Nowadays, for example, there is a wealth of information on maintaining books: “To keep out worms and mold, it is necessary to circulate clean air freely to avoid the accumulation of humidity. To do this, consideration should be paid to the location of vents (i.e., preventing the direct exposure of materials to air), the arrangement of bookshelves and the maintenance of space between books on shelves and walls.” (Nobukazu Mushanokoji, 1985, Preservation Measures for Libraries, Preservation Methods and Measures for Library Materials, Nichigai Associates, Inc.) Clark’s suggestions were not far from the common wisdom of the present day. It must have been easy for Clark – a scientist – to point out conditions like these.

[4]

Clark also talked about the windows and stairs:

“All the windows on the west side should be boarded up and cases or shelves for books arranged along both sides of the upper room.

The glass windows in the ends should be cut down two feet and then furnished with two sashes in each, hung by weights. The bars on the outside should be removed, as they furnish no protection and obstruct the light.

The stairs should be changed both in style and location, as they now occupy a large part of the center of both stories.”

The library had 3,734 foreign books and 5,100 Japanese and Chinese books in 1877 (Akizuki et al., 1980). Did Clark intentionally make an issue of the arrangement of the shelves and the daylight for reasons of book circulation?

The Japan Gazette was an English daily newspaper that was first published in 1867 and distributed in Yokohama. It included news coverage of Sapporo Agricultural College twice, on January 20 and 27, 1880, both times under the title of “Agricultural education in Japan.” The January 27 article described the library building as follows:

There is a small two-story building used as a library. It is obvious from its design that the building is the construction of a local architect. It cannot be praised the same as the other buildings. Furthermore, it lacks the primal elements of a library – good daylight and ventilation.

It is interesting that the article’s view coincided with that of Clark.

Here, let us take a look at part of a letter (dated September 20, 1877) sent to President Zusho by W. Wheeler, who served as Vice-President of the college after Clark’s departure.

“The wooden library-like building whose construction began in the absence of consultation with the teachers last year is inconvenient for its location. In addition, not only does it have air going through it, but it is also particularly unsafe. If a fire breaks out in the neighborhood, such a building will serve as a medium to readily spread the flames.”

What does the phrase “in the absence of consultation with the teachers last year” imply here? Dr. Clark wrote the following in a letter (dated November 19, 1876) to his young brother-in-law, Churchill.

“We are currently constructing a library. We already have quite a large collection of textbooks and encyclopedias. Is it possible to ask you to help us obtain appealing religious books in some way? Do you think you can get that weekly report in binding? If you could send it to me to the address of the Development Commission, I am willing to pay 50 dollars as part of the costs for sending religion-related literature in a package. And I can certainly arrange for the books to be labeled and stored in the agricultural college library.” (Ota, 1979)

From the letter, it is reasonable to think that Clark had some amount of information on the library under construction. It is, however, uncertain how much knowledge he had. Having done in just 250 days the same amount of work as people usually do in a lifetime (Maki, 1978), he may not have had time to spend on the details of the library. It seems certain that he had some involvement in the process of its construction that was more than could be described by the phrase “in the absence of consultation with the teachers.”

Aerial view of Sapporo Agricultural College (Development Committee (Ed.), Topography of Hokkaido)

[5]

Clark concluded the letter with words that can be understood as his views on books.

“Books are the implements of the student, and are worthy of most excellent treatment both on account of their cost and their intrinsic value. Therefore, I feel a deep interest in the College Library.”

These words correspond to following publication in the First Annual Report of Sapporo Agricultural College, 1877.

“There are many new literary and scientific works that are essential to provide to teachers and students. Books are their implements, without which they can do but little.”

In these words, the part “Books are their implements,…” was originally written by Dr. Clark. In Clark’s letter, I used the Japanese word “yougu” as a translation for “implements,” which was translated as “kigu” in the annual report. These translated words do not simply mean machinery-type equipment. As described in the words “new literary and scientific works” just before its appearance, it is clear that he regarded books as indispensable tools for thinking and developing character. In the inventory of books contained in the First Annual Report of Sapporo Agricultural College, 1877, multiple copies of several different books titled Natural Philosophy, On Liberty by J. S. Mill, and Complete Works by Shakespeare were listed (this inventory was omitted in the Japanese translated version Dai-ichi Nenpo). Additionally, in a letter Clark sent to Shosuke Sato (dated April 21, 1878) after arriving back home, he wrote, “Nature as a wonderful book and a book of books (the Bible) which they can learn from in such blessed environments” (Sato, et. al., 1986). These insights tell us that Clark placed significant emphasis on books and recognized the role of libraries as a place to deal with them.

Takashi Fujishima described the establishment as below in the Sapporo Agricultural College section of The History of Libraries in Hokkaido (1).

“The library staff consist of one person in the foreign book department (Retsu Igawa) and one in the Japanese and Chinese book department (Fuzan Nagao). The library is equipped with newspaper tables, desks, chairs, etc., and 20 Japanese newspapers are available. It is open to teachers, students and development committee officers from eight in the morning to sunset. (Fujishima, 1972)

This description refers to the reading room (dokushobo) set up in the North Hall in September 1877 and not to the library itself (i.e., the book storehouse), but it reminds us of how people used the library in the old days. A scene comes to mind in which time flows slowly over a broad open space while people enjoy reading and walking.

[6]

Based on the letter written by Clark, the Sapporo Agricultural College Library was overviewed. Although the building was quite poor and had no scenic attraction in the present perspective, it might have acted as a space for literary scholars where Haiku like “Sheltered by the shadow of the library, a fresh cool breeze blows” could be created, as long as it was a library. Books and words exhibit a power that is binding and captivating, and the sense of surplus that comes when people are freed from such powers must have been an important element for the library even at that time.

A suggestion from Takashi Fujishima of Hokkaido University Library (now Yamagata University Library) led me to study the letter written by Clark. Working on the difficult-to-read handwritten missives, I was confused by the profile of the educator W. S. Clark, as it seemed to appear and disappear repeatedly. I always feel frustration – a result of my lack of knowledge – and at the same time a kind of envy toward the past when I encounter a theme like this. I am forced to remember that the present is what we have now. It is of course true that what is here will change depending on how the time span of the present is set, but events that are talked about in terms of the past or history are subject to the phenomenon of being influenced by our imagination. Can past events be perceived without this motif? If the present is only for living in, it can be said that the past is only something to linger over. We might have been created only to recognize these events as a past that remains only in our imagination.

Note:

Clark’s letter quoted in this essay is a tentative translation based on material typed by Fujiwara from the original version. The letter was also translated into Japanese at the time and included in an article entitled Remarks Regarding the Improvement of the Agricultural College Library, in The 100 Year History of Hokkaido University: Materials on Sapporo Agricultural College (1) (pp. 282 – 283).

This essay is a revised version (correcting printing errors, etc.) of an article published in Kita no Bunko Vol. 19 (Sep. issue, 1991). (Revised October 3, 1996)